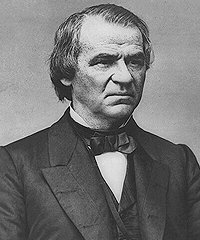

He was a self-educated man of humble origin who was Abraham Lincoln's vice president during his second term and became President upon the assassination of Lincoln in April of 1865.

He was a self-educated man of humble origin who was Abraham Lincoln's vice president during his second term and became President upon the assassination of Lincoln in April of 1865. Born to a poor family in Raleigh, North Carolina, as a boy Johnson never attended school. He was apprenticed to a tailor but ran away at age 16 and later settled in Greeneville, Tennessee, where he eventually set up his own prosperous tailor shop. He married Eliza McCardle, the daughter of a shoemaker, who helped him improve his reading, writing and math. They had five children.

Johnson discovered a flair for public speaking and entered politics, championing local farmers and small merchants against the wealthy land owners. He enjoyed a rapid rise, serving as a mayor, congressman, governor, and senator. Although he was a slave holder, he remained loyal to the Union and refused to resign as the U.S. Senator from Tennessee when the state seceded at the outbreak of the Civil War, which brought him to the attention of President Lincoln.

|

In 1862, Lincoln appointed him military governor of Tennessee. In an effort to win votes from Democrats, Lincoln (a Republican) chose Johnson (a War Democrat) as his running mate in 1864 and they swept to victory in the presidential election

Events Leading to Impeachment:

A series of bitter political quarrels between President Johnson and Radical Republicans in Congress over Reconstruction policy in the South eventually led to his impeachment.

Radical Republicans wanted to enact a sweeping transformation of southern social and economic life, permanently ending the old planter class system, and favored granting freed slaves full-fledged citizenship including voting rights.

The Radicals included such notable figures as Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. Most Radicals had been associated with the Abolitionist movement before the Civil War.

After the war, they came to believe whites in the South were seeking to somehow preserve the old slavery system under a new guise. They observed an unrepentant South featuring new state governments full of ex-Confederates passing repressive labor laws and punitive Black Codes targeting freed slaves.

Black Codes in Mississippi prohibited freedmen from testifying against whites, allowed unemployed blacks to be arrested for vagrancy and hired out as cheap labor, and mandated separate public schools. Blacks were also prohibited from serving on juries, bearing arms or holding large gatherings.

When the U.S. Congress convened on December 4, 1865, representatives sent from the South included the former vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens of Georgia, along with four ex-Confederate generals, eight colonels, six cabinet members and numerous lesser known Rebels. Northern congressmen, furious upon realizing this, omitted the southerners from the roll call and thus denied seats in Congress to all representatives from the eleven former Confederate states.

Radical Republican views gathered momentum in Congress and were in the majority by the end of 1865. In April of 1866, Congress enacted a Civil Rights Act in response to southern Black Codes. The Act granted new rights to native-born blacks, including the right to testify in court, to sue, and to buy property. President Johnson vetoed the Act claiming it was an invasion of states' rights and would cause "discord among the races." Congress overrode the veto by a single vote. This marked the beginning of an escalating power struggle between the President and Congress that would eventually lead to impeachment.

Bitter personal attacks also occurred with Johnson labeled as a "drunken imbecile" and "ludicrous boor," while the President called Radicals "factious, domineering, tyrannical" men. Unfortunately for Johnson, he had appeared drunk in public during his vice presidential inauguration. Weakened by a fever at the time, he had taken brandy to fortify himself but wound up incoherent and lambasted several high ranking dignitaries who were present.

In June of 1866, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing civil liberties for both native-born and naturalized Americans and prohibiting any state from depriving citizens of life, liberty, or property, without due process. The Amendment granted the right to vote to all males twenty-one and older. Johnson opposed the Amendment on the grounds it did not apply to southerners who were without any representation in Congress. Tennessee was the only southern state to ratify the Amendment. The others, encouraged in part by Johnson, refused.

Amid increasing newspaper reports of violence against blacks in the South, moderate voters in the North began leaning toward the Radicals. Johnson made matters worse by attempting to join all moderates in a new political party, the National Union Party, to counter the Radicals. To drum up support, he went on a nationwide speaking tour, but his gruff, uncouth behavior toward his political opponents alienated those who heard him and left many with the impression that Johnson's true supporters were mainly ex-Rebels. As a result, the Radicals swept the elections of November 1866, resulting in a two-thirds anti-Johnson majority in both the House and Senate.

With this majority, three consecutive vetoes by Johnson were overridden by Congress in 1867, thus passing the Military Reconstruction Act, Command of the Army Act, and Tenure of Office Act against his wishes.

The Military Reconstruction Act divided the South into five military districts under federal control and imposed strict requirements on southern states in order for them to be re-admitted to the Union including ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment and new state constitutions in conformity with the U.S. Constitution.

The other two Acts limited Johnson's power to interfere with Congressional Reconstruction. The Command of the Army Act required Johnson to issue all military orders through the General of the Army (at that time General Ulysses S. Grant) instead of dealing directly with military governors in the South. The Tenure of Office Act required the consent of the Senate for the President to remove an officeholder whose appointment had been originally confirmed by the Senate.

Many in Congress wanted to keep Radical sympathizer, Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, in Johnson's cabinet. The political feud between the President and Congress climaxed as Johnson sought to oust Stanton in violation of the Tenure of Office Act.

During a cabinet meeting in early August, Stanton had informed the President that the five military governors in the South were now answerable to Congress and not to the President and that the new military chain of command passed from the Commander of the Army through the House of Representatives.

On August 12, 1867, an outraged Johnson suspended Stanton and named General Ulysses S. Grant to replace him. However, the Senate refused to confirm Johnson's action. Grant then voluntarily relinquished the office back to Stanton.

On February 21, 1868, challenging the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act, Johnson continued his defiance of Congress and named General Lorenzo Thomas as the new Secretary of War and also ordered the military governors to report directly to him. This time Stanton refused to budge and even barricaded himself inside his office.

Three days later, the House of Representatives voted impeachment on a party-line vote of 126�47 on the vague grounds of "high crimes and misdemeanors," with the specific charges to be drafted by a special committee.

The special committee drafted eleven articles of impeachment which were approved a week later. Articles 1-8 charged President Johnson with illegally removing Stanton from office. Article 9 accused Johnson of violating the Command of the Army Act. The last two charged Johnson with libeling Congress through "inflammatory and scandalous harangues."